What would it take to break the Australian version of the bonds that caused the GFC…

When Paramount acquired the film rights to Michael Lewis’ nonfiction financial thriller The Big Short, it is unlikely they knew the impact they would have on the public’s understanding of finance. The 2010 blockbuster of the same name used an all-star cast and a scathing sense of humour to educate the masses on the origins of the Global Financial Crisis. Applauded for its historical accuracy, the film left many with a severely sour taste in their mouth at the protagonists’ priority of profit.

No punches are pulled during its explanation of subprime lending, collateralised debt obligations and credit default swaps. Of particular concern were mortgage-backed securities, which lay at the epicentre of the collapse. In the movie, their structures are likened to toppling Jenga towers and their contents to stews of rotting fish.

The disparaging approach is understandable given the economic, social and political cost of the Crisis. A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco in 2018 found that the financial cost amounted to $70,000 for every single American[1], while another study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland estimated that over 3.8 million Americans lost their homes as a result[2].

No rated Australian mortgage bond in history has ever suffered a permanent loss of capital.

By comparison, the Australian residential mortgage-backed security (RMBS) market weathered the storm of the Financial Crisis incredibly well. No rated mortgage bond suffered a permanent loss of capital. In fact, this is true for the Asian Financial Crisis, the Dotcom Bubble and the COVID Pandemic. No rated Australian mortgage bond in history has ever suffered a permanent loss of capital.

The legal frameworks and lending standards supporting securitised assets in Australia are particularly stringent and onerous when compared to other jurisdictions. This is to the benefit of investors and is a key reason why Australian RMBS should not be compared to the GFC mortgage bonds of the United States.

However, with a shift in central bank policy settings, it is reasonable to question what it would take to break an Australian RMBS. What would Michael Burry be looking for if he were to set his sights on the Australian RMBS market?

As a reminder, an RMBS is a type of financial instrument that is created by pooling together a large number of residential mortgage loans and then selling the rights to receive the cash flows from those loans to investors in the form of bonds or other securities. In essence, an RMBS is a way for investors to gain exposure to a diversified portfolio of loans secured by first-ranking mortgages, with the income generated from the mortgage payments being used to pay interest and principal on the bonds.

The right to repayment of the loans and the mortgaged properties form the security for the holders of the RMBS. In the event of default on a loan, the mortgaged property can be repossessed and sold, with the proceeds paying off any outstanding amounts owed.

Therefore, two factors that can determine the probability and severity of loss in an RMBS are mortgage defaults and house price declines.

Understanding the Impact of Mortgage Defaults and House Price Declines

Credit rating agencies, such as S&P Global Ratings, use sophisticated, individual loan-level data models to calculate standardised ratings for RMBS assets. By reverse engineering these models, it is possible to back solve for the assumed level of defaults and house price declines that these rated bonds can withstand before their capital begins to be eroded.

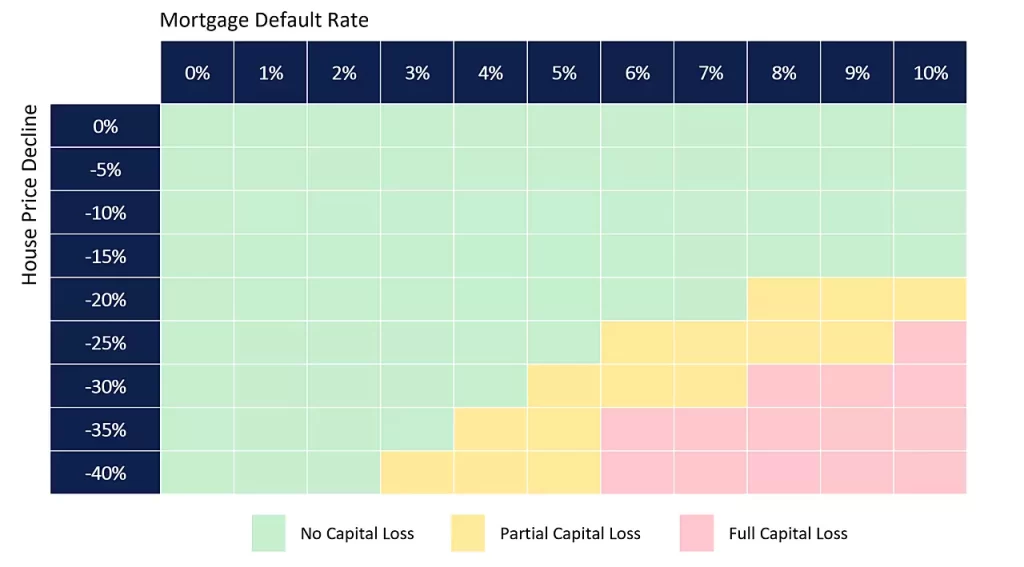

Our analysis used S&P Global Ratings’ Australian RMBS methodology to determine the magnitude by which default rates needed to rise and house prices needed to fall for investors in an archetypical RMBS to experience a loss. Our analysis found that for a BBB-rated mortgage-backed security to be wiped out, default rates would need to exceed 8% and house prices would need to decline by 30%. The below table allows you to explore your own stress test scenarios.

What’s interesting about our results is the joint nature of these two factors. House price declines alone are not enough to result in RMBS losses. If house prices fall, borrowers can opt to service their mortgage and await a recovery in asset prices instead of crystallising a loss. Similarly, if default rates increase while house prices fall only modestly, then the underlying properties can be sold for amounts in excess of the outstanding loans, albeit at the expense of the homeowner’s equity.

Mortgage defaults or house price declines in isolation do not cause a loss in an RMBS, you need significant levels of both.

To put this analysis into context, prime 90+ days arrears in Australia, that is borrowers who have missed more than three consecutive months of mortgage repayments, is 0.35%[3]. The highest arrears on record were during the GFC, reaching 0.80%. Importantly, arrears are not defaults. The proportion of mortgages where the lender has taken possession of the property is only 0.02%[4].

Given mortgages in Australia are full recourse, strategic default is almost unheard of, unlike in the US. The key reason why borrowers would stop making mortgage repayments is because of a prolonged loss of income. Unemployment would need to rise significantly from its current record low of 3.5% in order for default rates to exceed 8%. The Reserve Bank of Australia is acutely aware of this dynamic and watches the unemployment level like a hawk, particularly when it’s behaving like one.

Furthermore, the level of house price decline in an RMBS is relative to the date at which the bond was issued. The market consensus is that the peak-to-trough change in house prices will be in the range of 15-25%. However, this decline is only fully relevant for an RMBS issued on the day of the peak. RMBS issued on either side of the property price peak would experience a shallower price decline than the peak-to-trough figure reported in news headlines.

The mean house price in Australia increased by more than 20% over the 12 months leading up to the recorded peak in March 2022[5]. A 25% retracement from this peak would leave house prices at September 2020 levels. Therefore, any RMBS issued prior is unlikely to be impacted by this expected collapse in house prices and even those issued in the last two and a half years are likely to experience more muted declines.

Conservative assumptions mean the chance of capital loss is even lower than the table above suggests.

Lastly, the loss severity calculations make some conservative assumptions. For example, in Australia, it is a requirement that all prime mortgages with an LVR of greater than 80% have Lenders Mortgage Insurance. The table above does not take LMI claims into consideration, despite it being an additional source of recourse for RMBS investors in the event of default.

The loss table also excludes excess spread, which is the monthly excess revenue generated from the underlying mortgages once all necessary payments have been made to the RMBS investors. This cashflow represents the profit of the originator of the underlying loans. Often overlooked, excess spread enhances the credit quality of the securitised assets. If losses occur, this profit is contractually redirected to investors who were impacted. The excess spread continues to flow to these investors each month until the loss is cured. Therefore, excess spread provides not only a buffer against losses, but also a powerful incentive to ensure originators have confidence in the repayment of the loans they issue.

These models are developed using excessive caution, meaning the analysis underestimates the capital protection qualities of these bankruptcy remote vehicles. The inclusion of these factors would reduce the likelihood of partial and full capital loss.

In Australia, strict lending standards, tested securitisation structures and heavy regulatory oversight mean that residential mortgage-backed securities are less exposed to the systemic risks portrayed in The Big Short. The importance of real estate to our financial system means there is strong economic, social and political alignment in supporting homeowners and their most crucial asset. While Michael Burry and others developed the means by which to bet against the housing market, it seems unlikely that this same strategy would pay off in Australia any time soon.

[1] Barnichon, R., Matthes, C. and Ziegenbein, A. (2018) The Financial Crisis at 10: Will we ever recover? Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Available at: (VIEW LINK)

[2] Dharmasankar, S. and Mazumder, B. (2016) Have Borrowers Recovered from Foreclosures during the Great Recession? Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Available at: (VIEW LINK)

[3] S&P Global Ratings (2023) Australian RMBS Arrears SPIN Statistics January 2023 (Exc. Non-Capital Market Issuance) as at 31 January 2023.

[4] APRA (2023) Quarterly Authorised Deposit-Taking Institution Property Exposures Statistics – March 2004 to December 2022 as at 31 December 2022.

[5] Core Logic (2023) Corelogic Daily Home Value Index as at 28 February 2023.

Disclaimer

This commentary is prepared by Aquasia Pty Ltd ABN 20 136 522 051, AFSL 337872 (Aquasia) for general information purposes and does not constitute financial or investment advice or recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any financial product. It does not take into consideration any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs and should not be used as the basis for any investment or financial decision. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.